Book Review: Seven Fallen Feathers by Tanya Talaga

Toronto Star journalist Tanya Talaga takes a dive into a crisis based in the northern community of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Since the year 2000, seven Indigenous high school students have died in circumstances that are too similar to discount. Questions around the events leading to their deaths remain unanswered to this day. In every case, it was found that the police systematically failed to provide the families with due process and a sense of justice. In the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's (TRC) final report in 2015, Seven Fallen Feathers is required reading.

At the heart of this essay is the Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School in Thunder Bay. The school is for aboriginal students and has been run by the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council (NNEC) since its opening in the year 2000. The school’s mandate is to develop a sense of identify for First Nations youth, while providing a learning environment where they can advance their education. The school welcomes students from thousands of kilometres away given the geographical location of many Indigenous communities in Northern Ontario. Students often must leave their families in order to go to school, finding arrangements in boarding houses or relatives for a place to stay.

As a result of leaving their families in order to pursue an education and hope for a better future, seven youths lost their lives. Their names: Jethro Anderson, Curran Strang, Paul Panacheese, Robyn Harper, Reggie Bushie, Kyle Morrisseau, and Jordan Wabasse.

Through an exploration of the history and surroundings of Thunder Bay, Talaga carefully constructs the stories of each student. She collects facts that were made available through police reports, interviews, and, ultimately, the inquest into the deaths of seven students. But there’s more: she also weaves in historical information that sets the context for the realities faced today. Through the stories of each student, we also read about the intergenerational trauma at play within Aboriginal communities as a result of the residential school program. She explains Jordan’s principle and the government’s failed commitments when it comes to accessing health care and education for Indigenous youths. She highlights the mountain of work and evidence brought to light by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Talaga’s work brings stories to the fore when mainstream media have covered them up for decades: “Families are still being told—more than twenty years after the last residential school was shut down—that they must surrender their children for them to gain an education. Handing over the reins to Indigenous education authorities such as the NNEC without giving them the proper funding tools is another form of colonial control and racism.”

The 94 recommendations published by the TRC two years ago have yet to be implemented. In the spirit of engaging in an ongoing process of reconciliation, Tanya Talaga provides the analysis and knowledge needed to strive for a hopeful future for Indigenous communities in Canada. Learning about the situation in Thunder Bay is a responsibility of all Canadians to face the facts when it comes to the treatment of First Nations peoples—in history, yes—but also today in our current world and province.

Seven Fallen Feathers is a difficult read. It deals with death and racism; it tackles pain and suffering head on. Telling the students’ stories is also an act of hope and healing based on the certainty that things can be better, and that they must. This book is a solid piece of investigative journalism and should be read, and shared far and wide.

5/5

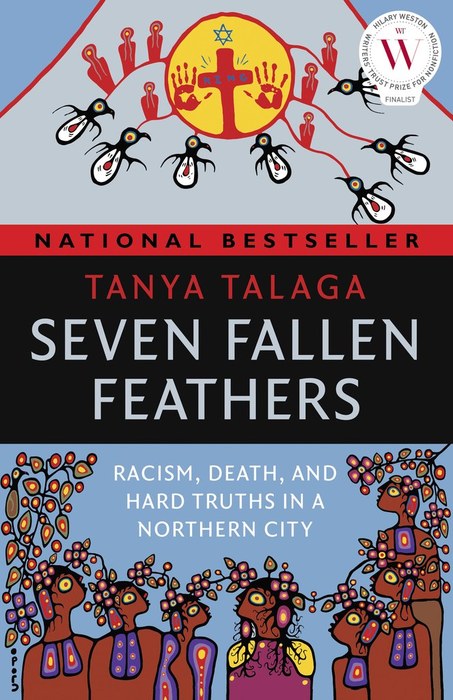

Seven Fallen Feathers by Tanya Talaga

Truth and Reconciliation Commission